- · 4847 friends

Mother Disputes Interim Parenting Orders

Pilot & Silver [2022] FedCFamC1A 191 (21 November 2022)

The mother appeals from interim parenting orders providing for the children to live with the father and spend professionally supervised time with her. The Court, in resolving this dispute, relied upon tested evidence of the Court Child Expert.

Facts

The litigation between the parents was commenced by the father in the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (as the Court was then known) on 5 September 2018 when the children were 18 months old. As recorded by the primary judge, during the course of those proceedings the mother made extensive and significant allegations that the father had occasioned serious family violence and abuse towards herself and the children. It was her case that the children were exposed to an unacceptable risk of harm in the father’s care. Notwithstanding those allegations, final consent orders were made on 19 October 2020 (“the final orders”) providing for the parents to have equal shared parental responsibility for the children, for the children to live with the mother and to spend substantial and significant time with the father, expanding to each alternate weekend from after school on Thursday to before school on Monday, during school holidays and on special days.

Proceedings were recommenced by the father on 30 May 2022. He sought orders for sole parental responsibility of the children and that the children live with him. On an interim basis he sought that the mother’s time with the children be professionally supervised. The primary judge recorded that the father’s Initiating Application was made against a background of the mother retaining the children in early May 2022, the parenting arrangements regulated by the final orders thereafter breaking down, and the mother replicating a pattern of behaviour of making allegations to multiple agencies as to the father being physically and potentially sexually abusive towards the children (at [15]).

The mother filed a Response resisting the father’s application. She sought orders that she have sole parental responsibility for the children and that, at least in the interim, the father’s time with the children be professionally supervised. By way of their applications, both parents sought significant variations to the final orders on an interim basis. On 30 May 2022, orders were made pursuant to s 69ZW of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) (“the Act”) requesting information from the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (“the Department”). On 8 June 2022 the matter came before another judge of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1).

A Child Protection co-located worker attended on that day and gave the Court information as to the involvement of the family with Child Protection (as recorded by the primary judge at [22]). The Court was informed that Child Protection was undertaking an investigation into the family and held current concerns as to the mother’s mental health and as to the mother putting the emotional and psychological wellbeing of the children at risk. The Court was further informed that while the Department did not have concerns for the children in the father’s care, they did have concerns about a developing pattern of the mother making seemingly “unsubstantiated or baseless allegations of harm to the children in the father’s care”. Material produced on subpoena was tendered into evidence before the primary judge.

That material recorded that SOCIT had interviewed the children, who made no disclosures that required further action. It also recorded that the maternal grandmother had taken one child to City N Police Station on 9 May 2022, that the mother had some interaction with City KK SOCIT in May 2022, and that she had taken the children to LL Town Police Station on 16 May 2022. The police interviewed the children at their kindergarten on 23 May 2022. On 7 July 2022 the Child Impact Report was released to the parents after the Court Child Expert interviewed the children individually on 27 June 2022.

That report made no recommendations as to the children’s living arrangements, save to say that the orders then in place (being those made on 8 June 2022) were sufficient to maintain a relationship between the mother and the children and that it may be premature to make any orders as to parental responsibility. The reasons record the expert’s concern that the children have been subjected to multiple investigations, multiple interviews and multiple disruptions. Both of the children were able to identify positives about their parents which included physical affection. It seemed to [the Court Child Expert] at least that they did not have any significant complaints about either parent.

It was both the mother and the father’s case before the primary judge that the other presented an unacceptable risk of harm to the children, and that such risk could only be mitigated if the other’s time with the children was limited and professionally supervised. The ICL sought orders in similar terms to those sought by the father, contending that the risk posed to the children by the mother was that identified by the father.

Issue

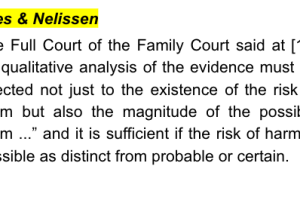

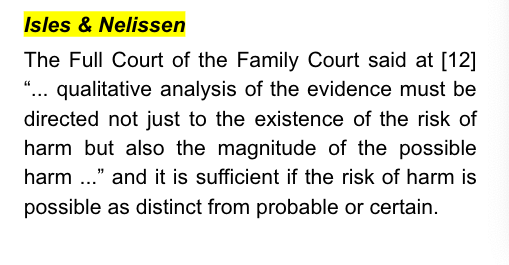

Whether or not the primary judge correctly applied principle as to the identification and assessment of unacceptable risk.

Applicable law

Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) s117 - warrants a costs order in favour of the ICL and the father.

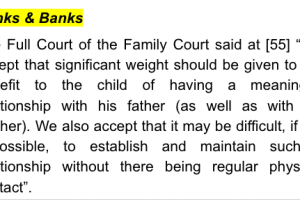

Banks & Banks (2015) FLC 93-637; [2015] FamCAFC 36 - where the Full Court of the Family Court said at [55] “We accept that significant weight should be given to the benefit to the child of having a meaningful relationship with his father (as well as with his mother). We also accept that it may be difficult, if not impossible, to establish and maintain such a relationship without there being regular physical contact”.

Analysis

The mother submitted than an assessment of risk involves a sequential weighing of “two factors”, being the likelihood of the asserted risk and, subsequently, its magnitude. Hence the gravamen of her complaint as argued was that the primary judge fell into error in that having considered the “likelihood of the asserted risks”, she failed to then consider the severity of those risks. The mother submitted in the appeal hearing that the reasons of the primary judge did not explicitly consider the magnitude of the asserted risk. However, the reasons reveal that the primary judge explicitly accepted the premise on which the case was conducted by the parents and the ICL.

Although the primary judge turned her mind to other factors, she recognised that the decisive issue to be determined at this interim stage of the proceedings was how best to protect the children from potential exposure to an unacceptable risk of harm. The process of evaluation by the primary judge as to the probabilities of the competing claims was substantial, considered and correctly completed. The mother’s argument, if it were accepted, would require the primary judge to engage in mental gymnastics by separately considering the merits of the mother’s proposal for the children to spend unsupervised time with her, having already concluded that she posed an unacceptable risk to the children that could only be ameliorated if time spent was supervised.

Conclusion

The appeal is dismissed. Within 28 days of the date of these orders, the appellant shall pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal fixed in the sum of $11,217 and the Independent Children’s Lawyer’s costs fixed in the sum of $3,729.