- · 4844 friends

Appellant Opposes Property Settlement Orders

Grunseth & Wighton [2022] FedCFamC1A 132 (26 August 2022)

The primary judge made orders dividing the parties’ property so the appellant received 47.5 per cent and the respondent received 52.5 per cent. The appellant contends that such a finding could not be made because she contributed over half of the property to be divided. The Court, in making its orders, assessed if the primary judge erred in his findings.

Facts:

The appellant appeals from property settlement orders made by a judge of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) on 24 December 2021, which divided the parties’ property so that the respondent, Mr Wighton, received 52.5 per cent and the appellant, Ms Grunseth received 47.5 per cent. The appellant contends that such a finding could not have been made because she had contributed over half of the property to be divided, the other contributions also favoured her and a small adjustment in her favour. The parties met in 2004 and slowly developed a relationship which became a de facto relationship (as defined by s 4AA(1) of the Act) in late 2013. At that time, they purchased a property in B Town (“the B Town property”) for $1,040,000, which was financed, in part, by a mortgage of $99,223.50.

The appellant’s direct contribution to that purchase was $716,423.27, most of which came from the sale of a property previously owned by her. The respondent contributed $320,000, of which $20,000 came from his savings and $250,000 as a gift from his mother. The respondent’s father also made an immediate payment towards the mortgage of $50,000. The parties recognised these various contributions in the ownership of the home, which was registered in the name of the parties as tenants in common with 70 per cent held by the appellant and 30 per cent held by the respondent.

The respondent received inheritances in June 2015 of $750,000 and in September 2017 of $128,211.92, making a total of $878,211.92. On 17 June 2015, the respondent paid out the balance of the mortgage in the sum of $43,846.42. In January 2016, the respondent paid the appellant $160,000. In short, the respondent’s evidence was that this was pursuant to an earlier oral agreement to the effect that if he made that payment, he would become a one-half owner of the B Town property.

The appellant agreed that the payment was for an increased share of the property but not for equal shares because of the increase in value of the property. She said that no percentage increase was ever agreed. No adjustment to the nature of the registered ownership was made. The primary judge was persuaded that there probably was an informal agreement between the parties which led the [respondent] to deposit $160,000 into the [appellant’s] bank account, and her not to return it. However he was not persuaded that this is of great relevance, and that it is the actual contributions made, and their timings, in the context of the entire relationship which must be considered and weighed.

The parties separated in October 2016, although they both remained living in the B Town property until November 2019. The appellant was found to have made greater non-financial contributions than the respondent and there were no considerations under s 90SF(3) of the Act which required adjustments, save for “some allowance” in favour of the appellant “for her lesser total future earning capacity”. His Honour also found that, apart from the inheritances, the parties’ financial contributions throughout the relationship were equal.

Issue:

Whether or not the appeal should be granted.

Applicable law:

Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) ss 4AA(1) - provides that a person is in a de facto relationship with another person if:

(a) the persons are not legally married to each other; and

(b) the persons are not related by family (see subsection (6)); and

(c) having regard to all the circumstances of their relationship, they have a relationship as a couple living together on a genuine domestic basis.

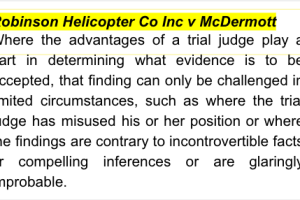

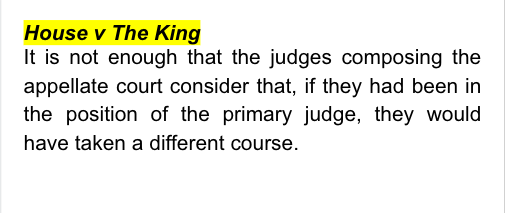

Analysis:

Not all of the respondent’s inheritances were reflected in assets available for division. Those that remained were the $160,000 in the appellant’s bank account, $399,137 in the respondent’s bank account and possibly a loan owed to the respondent in the sum of $30,000 (as well as the ‘notional’ property of $50,000). About $43,000 was used to pay out the mortgage. There was no evidence as to what happened to the rest.

The ultimate determination of a 47.5/52.5 per cent division cannot be reconciled with the central fact that the appellant contributed over 52.5 per cent of the overall assets and with assets to which the respondent made no contribution to at all. Professor N is a psychiatrist who provided a report in which he opined that the appellant had a post-traumatic stress disorder (“PTSD”) which was consistent with the family violence she had described to him. The primary judge formed the view that the [appellant’s] evidence on her mental state and the alleged impacts of family violence on her is unreliable, and as [Professor N’s] opinion can only be as good as the factual foundation on which it is based. The appellant also submitted that the finding of Professor N that she had PTSD bolstered her evidence because there was no other explanation for the disorder. However, as Professor N’s report makes plain, it is based on an acceptance of the appellant’s allegations.

The primary judge found that the appellant was the registered owner of Roxy, a Spoodle, who had paid for her and was her legal owner. With respect to the payment of Roxy, the appellant’s evidence was that she paid for Roxy, her desexing operation, registration, food, vaccinations, medications and grooming. It does appear that there was a mutual intention of the parties that Roxy was purchased for Ms T, the respondent's daughter from a previous relationship, which is consistent with the respondent’s evidence that he tried to register Roxy in Ms T’s name before she turned 18 years of age. Ms T is not a party to the proceedings and has no legal or equitable interest in Roxy, and therefore it is not appropriate for the Court to make an order transferring Roxy to Ms T.

Conclusion:

The appeal is allowed. Orders 10(b), 14 and 15 made on 24 December 2021 are set aside. Orders are made to adjust the split in sale proceeds upon the sale of the property. The appellant is to retain the dog. The respondent is to pay the costs of the appellant in a fixed sum.