- · 4666 friends

Appellant Opposes Property Division Orders

Morgan & Valverde [2022] FedCFamC1A 133 (31 August 2022)

The primary judge made final orders dividing the property between the parties. The evidence at trial comprised only that of the wife as the husband failed to file and serve any evidence. The Court, in determining whether the appeal should be granted, assessed the effect of the husband’s failure to adduce evidence-in-chief.

Facts:

In January 2019, the parties ended their de facto relationship. The primary judge found the relationship endured for about nine years (at [11] and [87]), but considered their capital contributions from only the commencement of cohabitation some seven years beforehand (at [13] and [17]–[18]). The parties had no children and each was gainfully employed for portions of the relationship. In 2012, the parties jointly acquired a parcel of real property (“the Suburb B property”), assisted by bank finance secured by mortgage.

The husband has occupied the property to the wife’s exclusion since their separation. In 2017, the husband established a self-managed superannuation fund and was the sole shareholder and director of the corporate trustee. Proceedings for property settlement were commenced by the wife in November 2019. There was no dispute about the existence of jurisdiction to entertain the dispute. The primary judge found that the wife had property with a net value of $241,671 and superannuation of $143,085, totalling $384,756.

Against the established background of the husband’s repeated failure to give proper financial disclosure, the primary judge found he had property with a net value of $273,772 and superannuation of $512,000, totalling $786,172. The husband’s property and superannuation was worth more than double that of the wife. The Suburb B property was by far the most valuable asset. On the evidence which was adduced by only the wife, the primary judge found an adjustment of the parties’ property interests would be just and equitable.

Her Honour determined that a just and equitable division of their property would result in the husband taking 57.5 per cent and the wife 42.5 per cent of the assets and superannuation. To effect the division, the parties kept their own superannuation entitlements, but the wife took a greater share of the net proceeds which were expected to be yielded by the sale of the Suburb B property.

Issue:

Whether or not the primary judge failed to afford the husband procedural fairness.

Applicable law:

Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia Act 2021 (Cth) s 69 - using express statutory power to place limits on the length and breadth of cross-examination is an entirely different thing from denying an opportunity to cross-examine altogether.

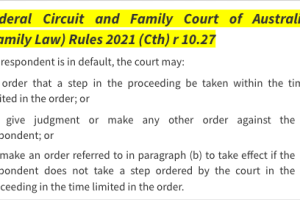

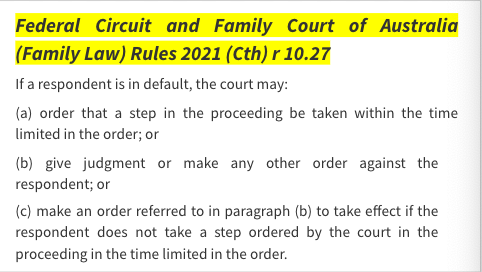

Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Family Law) Rules 2021 (Cth) r 10.27 - provides that if a wife is in default, the court may:

(a) order that a step in the proceeding be taken within the time limited in the order; or

(b) give judgment or make any other order against the wife; or

(c) make an order referred to in paragraph (b) to take effect if the wife does not take a step ordered by the court in the proceeding in the time limited in the order.

Goldsmith v Sandilands (2002) 190 ALR 370; [2002] HCA 31 - provides that if allowed to cross-examine the wife, the husband would have been bound by her answers to his questions, at least to the extent her evidence was accepted by the primary judge as being credible and reliable, since he led no contrary evidence to positively establish his own version of events.

Re F: Litigants in person guidelines (2001) FLC 93-072; [2001] FamCA 348 - provides that a judge should inform the litigant in person of the manner in which the trial is to proceed, the order of calling witnesses and the right which he or she has to cross examine the witnesses.

Stead v State Government Insurance Commission (1986) 161 CLR 141; [1986] HCA 54 - provids that where, however, the denial of natural justice affects the entitlement of a party to make submissions on an issue of fact, especially when the issue is whether the evidence of a particular witness should be accepted, it is more difficult for a court of appeal to conclude that compliance with the requirements of natural justice could have made no difference.

Analysis:

The wife’s evidence was unchallenged, but it is not apparent from either the transcript or the reasons for judgment why that is so. The husband’s failure to adduce evidence-in-chief need not have precluded him from being able to test the wife in cross-examination about those aspects of her evidence which he disputed. The “evidence” the husband admitted he did not then have “to put” was the affidavit material he had failed to file in breach of procedural orders. In the appeal, the wife submitted the concession should be imputed to mean the husband had no documents to tender in evidence either, but the submission is rejected as it would flatly contradict the husband’s assertion in the appeal that he was armed with documents at the trial, which he regarded as being relevant and probative.

His assertion cannot be just disregarded as being false without a legitimate basis – and there is none. Significantly, the husband confirmed to the primary judge that he disagreed with the evidence adduced and the submissions made by the wife. He challenged the case she put. Although the husband did not specifically ask to cross-examine the wife, he had already been told he would not be allowed to do so and, absent legal representation, he meekly did not contest the ruling.

Conclusion:

The appeal is allowed. The proceedings are remitted to the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) for re-hearing of the cause between the parties for relief under Pt VIIIAB of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).