- · 4735 friends

Mother Opposes Parenting Orders in Favor of Father

Shell & Armel [2022] FedCFamC1A 83 (3 June 2022)

Orders were made changing the parent with whom the children of the relationship lived from the appellant mother to the respondent father, and restraining the mother from spending any time with the children for a period of 12 weeks before introducing arrangements for the children to spend time with her. The mother appeals from these orders. The Court, in resolving this dispute, assessed whether the primary judge erred in the findings of fact.

Facts:

The parents commenced cohabitation in 2011 and separated finally in early to mid-2016. There are twin children of the relationship, X and Y, born in 2011, who are now 11 years of age (“the children”). At trial, the father sought orders for a change of the children’s residence, maintaining that such an order was necessary because the mother had alienated the children from him. The mother sought orders that the children live with her and spend no time with the father.

The children were resistant to spending time with the father. The mother argued that this was a consequence of their realistic estrangement from the father due to family violence and abuse, to which she asserted they had been exposed. Each parent sought sole parental responsibility for the children. The ICL sought orders, inter alia, that the father have sole parental responsibility for the children; that the children live with him; that the mother be restrained from spending any time with them for a period of 12 weeks; and that thereafter the children spend graduated, increasing time with her, culminating in alternate weekends.

Following separation, the children lived with the mother and generally spent time with the father one day on the weekend. However, the mother’s case was that, by September 2016, the children became increasingly resistant to spending time with the father and that changeovers were extremely traumatic for all involved. The father instituted these proceedings on 7 March 2017. Orders were made providing for the children to spend time, including overnight time, with the father.

From January 2018, the time they spent with him was in the company of the mother and did not include overnights, with the mother insisting that it occur in a public place. However, in January 2019, the parents and children travelled overseas together for a holiday. Notwithstanding the mother’s allegations of family violence and abuse, she saw fit to be in the presence of the father, both on this regular basis, as well as overseas. In late April 2019, the mother stopped attending the children’s time with the father.

On 14 August 2020, after the release of a Family Report, interim orders were made for the father to spend time with the children two hours per fortnight, professionally supervised, and for the parents and children to participate in family therapy. Further interim orders were subsequently made for him to spend time with them for two hours, once a month, with changeovers to occur at a shopping centre. It is from those orders that the mother appeals.

Issues:

I. Whether or not there was a denial of procedural fairness.

II. Whether or not the primary judge erred in findings of fact.

Applicable law:

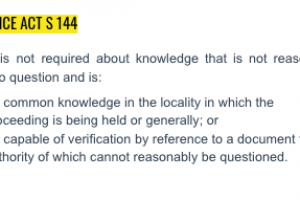

Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 144 - provides that proof is not required about knowledge that is not reasonably open to question and is:

(a) common knowledge in the locality in which the proceeding is being held or generally; or(b) capable of verification by reference to a document the authority of which cannot reasonably be questioned.

Analysis:

It is evident that the Family Consultant had read and understood, albeit in a general sense, the Johnson and Kelly article referenced by the primary judge. However, she was not asked, either on behalf of the ICL or either of the parents, whether she adopted the article, nor did she expressly or implicitly do so, in whole or in part. Whilst, in cross-examination by the ICL, the Family Consultant made observations as to the behaviours of the mother, the father and the children and, in the case of the children, their beliefs, within the rubric of the three organising beliefs put to her, she did not express any view as to the appropriateness or otherwise of adopting theories postulated in the article, either generally or in relation to the three beliefs. No objection was taken by the mother’s counsel to this line of questioning, nor was any call made for the article, “the report writer’s evidence with respect to the ‘organising beliefs’ as set out in the paper and her answers went into evidence unopposed”.

The article was not tendered into evidence. The matters therein manifestly are “reasonably open to question” and are neither “common knowledge in the locality in which the proceeding is being held or generally”, nor are they “capable of verification by reference to a document the authority of which cannot reasonably be questioned”. The ICL or, indeed, the father could have sought to tender the article into evidence but neither sought to do so, albeit that any such attempted tender may have been met with a successful objection thereto.

Conclusion:

The appeal is allowed. The proceedings are remitted to the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) for re-hearing by a judge other than the primary judge. The appellant mother is granted a costs certificate pursuant to the provisions of s 9 of the Federal Proceedings (Costs) Act 1981 (Cth). The respondent father is granted a costs certificate pursuant to the provisions of s 6 of the Federal Proceedings (Costs) Act 1981 (Cth). The Court grants to both the appellant mother and the respondent father costs certificates pursuant to the provisions of s 8 of the Federal Proceedings (Costs) Act 1981 (Cth).